March 10, 2009

My heart flutters as I begin my first week here at Movie Morlocks. I’ll need time to settle into my new Tuesday digs before I can work out any cinephilic kinks, so please forgive my youthful enthusiasms and wild hyperbole. I’ll settle down eventually, but not quite yet.

My heart flutters as I begin my first week here at Movie Morlocks. I’ll need time to settle into my new Tuesday digs before I can work out any cinephilic kinks, so please forgive my youthful enthusiasms and wild hyperbole. I’ll settle down eventually, but not quite yet.

Let’s get the introduction out of the way. By general life expectancy standards, I’m young, so the current economic crisis hasn’t destroyed my non-existent wealth. Any previous possibility of easy living was scuttled by my decision to attend NYU to study cinema. Bad move! Now destitute, my only solace is the moving image and the multifarious pleasures it brings. That’s what I’ll be writing about here, hopefully in a lucid and engaging manner.

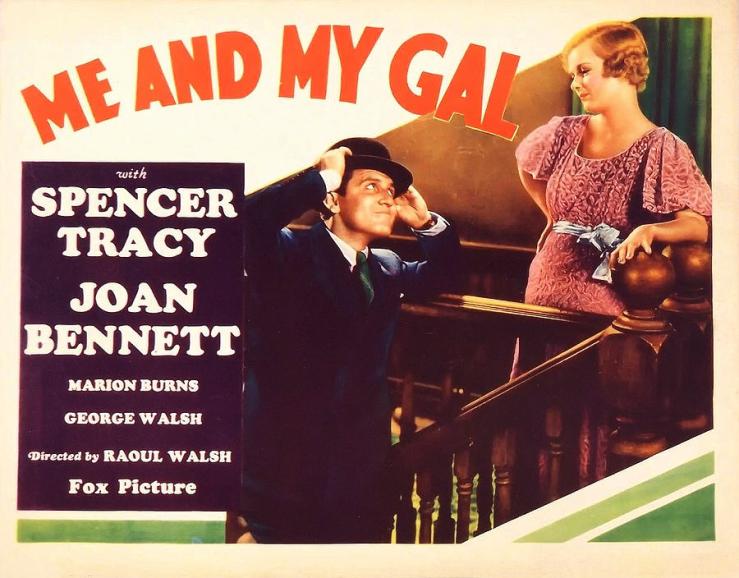

Speaking of economic devastation, Film Forum in NYC has recently concluded a wonderful series of Depression-era films entitled “Breadlines & Champagne.” An eclectic mix of social-realist dramas, high-society screwball comedies, and gangster operatics, it was a revelatory peek into the incredible richness and diversity of the films from that early sound, pre-code period. I received the greatest kick from Raoul Walsh’s unclassifiable 1932 experimental gangster- romantic comedy, Me and My Gal.

I initially sought it out because it was a particular favorite of Manny Farber, the brilliant painter and film critic who passed away last year. He has an essay on Raoul Walsh in his invaluable collection, Negative Space, in which he names Me and My Gal as his favorite Walsh film:

“The movie has a double nature, looking exactly like 1931 just after the invention of sound, and one that has queer passages that pop out of the storyline, foreshadowing the technical effects of 60′s films. These quirky inclusions, the unconscious oddities of a director with an unquestioning belief in genre who keeps breaking out of its boundaries, seem timeless and suggest a five-cent movie with mysterious depth.”

It is this “breaking out” that makes Gal so remarkable, a mash-up of styles and attitudes that never condescends to its material but wrings every possible variation out of it. The plot follows Spencer Tracy’s police officer, Danny Dolan, on the beat at New York’s Pier 13, as he woos waitress Helen Riley (Joan Bennett) while searching for escaped mobster Duke Castenega (George Walsh, Raoul’s brother). Duke is holed up with Helen’s sister Kate, and Dolan attempts to bring him in without destroying the family. It’s a fairly routine plot, lifted from a segment of the 1920 Fox film While New York Sleeps. The project went through a variety of hands before it landed with Walsh, having been previously attached to William K. Howard, Alfred Werker, and Marcel Varnel. According to the AFI reference book “Within Our Gates: Ethnicity in American Feature Films 1911 – 1960″, Walsh shot the film in a scant nineteen days, and he doesn’t even mention it in his rakish autobiography, Each Man In His Time.

Perhaps it’s the speed of the schedule that led to its inventive, magpie spirit. Plenty of material needed to be created on the spot (there was obviously little pre-production time), and the film is flooded with ideas (some borrowed, some new) – ideas for pratfalls, camera movements, parodies. The movie contains direct addresses to the camera (by a tight J. Farrell MacDonald), self-reflexive voice-overs, and endless bits of comic business, from Will Stanton’s drunk act to the stinging bon mots flung from Bennett to Tracy.

This was cinematographer Arthur Miller’s first job at Fox, which would eventually lead to his magnificent work with John Ford. In an interview with Leonard Maltin, he discusses a trick shot composed during a robbery sequence:

I had the camera on a rubber-tire dolly, and just hit it. Now, this wasn’t original, because I had seen the earthquake picture over at the Chinese theater, and I saw what effect it gave. That’s what they did all through it; you’d hear the rumble first, everything would start to shimmy, and then it would hit. They rolled their dolly.

It’s this kind of innovative spirit, repurposing industrial tricks on a smaller, what Manny Farber would call a “termite” level, that animates this consistently surprising film. Another techniqe Walsh borrows is the interior monologue, which was used extensively in Robert Z. Leonard’s 1932 adaptation of Eugene O’ Neill’s Strange Interlude, in which the majority of the drama was enacted in voice-over. A curiosity and a flop, it made for rich parodic material. The scene that elicited the biggest laughs at the screening I attended (big, roiling guffaws), was a priceless ironic take on this technique. Dolan is on his first date with Helen, and they end up alone at her apartment, after she winks away her eager-to-please dad (MacDonald). Dolan mentions a film he’s seen, “Strange Inner Tube”, and caddishly lays his head on her lap. They slide down next to each other on the couch when the voice-overs start, each reflecting on their seduction techniques while uttering only banalities to each other. Eventually Dolan psyches himself up to go for the lips, and dives in for a kiss. He receives a smack in return, and their combative courting process proceeds apace.

It’s a wonderfully funny sequence, playfully mocking the staid “prestige” pictures that would receive the big studio push this cinematic mutt would not. What truly makes it sing, though, are the performances from Spencer Tracy and Joan Bennett. Bennett is saucily obstinate, pursing her bow-tie lips before unleashing a cataract of insults. As for Tracy, well, he’s sublime, as is the rest of the cast, who spout a symphony of lower East Side argot that Walsh orchestrates with speed and brio. That’s one of the film’s major pleasures – it’s sense of place, which is another aspect Farber loved about it. He gets the last word:

It is only fleetingly a gangster film, not quite outrightly comic: it is really a portrait of a neighborhood, the feeling of human bonds in a guileless community, a lyrical approximation of Lower East Side and its uneducated, spirited stevedore-clerk-shopkeeper cast. There is psychological rightness in the scale relationships of actors to locale, and this, coupled with liberated acting, make an exhilarating poetry about a brash-cocky-exuberant provincial. Walsh, in this lunatically original, festive dance, is nothing less than a poet of the American immigrant.

[…] Cry (1955), and The Tall Men (1955) in quick succession with comment below, and my bits on Me and My Gal (1932) and Colorado Territory (1949) […]

[…] My Gal (1932), The Bowery (1933) and Sailor’s Luck (1933). 1932 was a good year. I wrote my first post here at Movie Morlocks on Me and My Gal, and lets see if it […]